By Mike Vladimir Chirwa

Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda’s life story is often simplified, mythologized, or distorted, yet a closer examination reveals a complex journey shaped by education, ambition, racial politics, and personal contradictions. After completing his high school education, Banda enrolled at the University of Chicago, where he earned a Bachelor of Philosophy degree in 1931. At a time when higher education for Africans was rare and deeply constrained by racism, this achievement alone marked him as an exceptional figure. His intellectual grounding in philosophy helped shape his disciplined worldview, his belief in order, and his later insistence on moral authority in leadership. Education was not merely a personal pursuit for Banda; it was a means of self-definition in a world that denied African excellence.

Following his undergraduate studies, Banda enrolled at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, one of the few institutions in the United States that trained Black doctors. He completed his medical degree in 1937. Tennessee, despite being part of the segregated American South, had a sizeable Black population, and Banda reportedly felt a sense of community and belonging there. Nonetheless, racism and racial segregation remained pervasive, limiting professional advancement and personal freedom for Black professionals. Banda would later reflect that while he could train in America, the social ceiling imposed by race made long-term practice deeply unattractive. His decision to leave the United States was therefore not a rejection of opportunity, but a strategic move to escape entrenched racial barriers.

In 1938, Banda relocated to Britain, entering his early thirties unmarried and entirely focused on professional advancement. His move coincided with a critical historical moment: Europe stood on the brink of the Second World War, which broke out in 1939. The looming conflict created an urgent demand for medical professionals, particularly as many white British doctors were conscripted to serve on the front lines. Banda seized this opening. He pursued postgraduate medical training in Scotland, earning advanced qualifications from the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons by 1941. These credentials were not merely academic achievements; they were passports to legitimacy within the British Empire’s medical establishment.

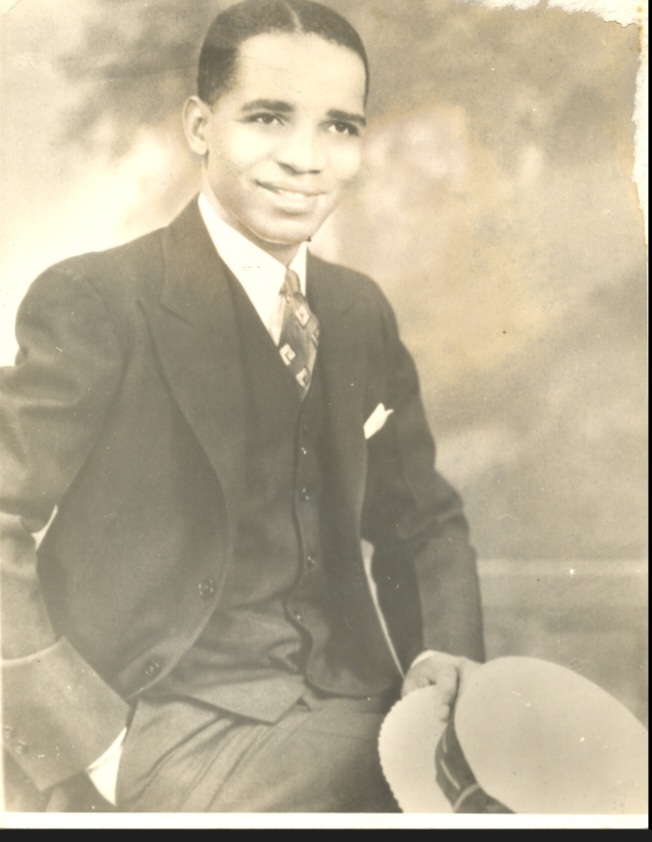

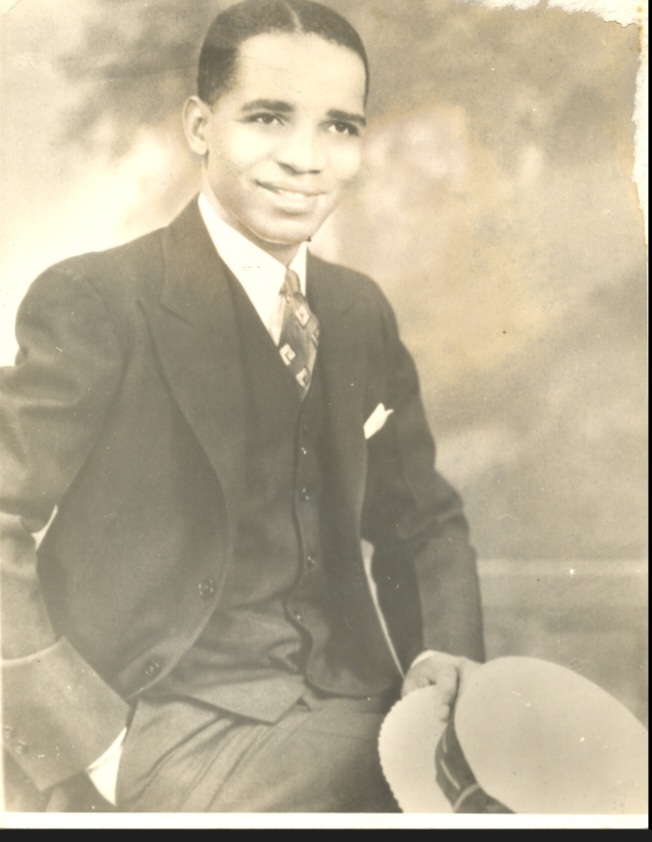

Chanco News…..Banda in his early days. -1940s

Chanco News…..Banda in his early days. -1940sOne of the primary reasons Banda pursued further studies in the United Kingdom was to qualify for medical practice across the British Empire. At the time, British-recognized medical credentials carried immense authority and mobility. Unlike the United States, Britain though not free from racism offered Black professionals comparatively greater professional latitude, especially during wartime. Banda understood the imperial system well and positioned himself carefully within it. His medical career flourished in Britain, and he established himself as a competent and respected physician, even as he remained socially isolated and intensely private.

However, Banda’s time in Scotland was not without controversy. He eventually left under the cloud of a scandal involving a white woman reportedly the wife of one of his church acquaintances whom he impregnated. The incident was deeply embarrassing in a conservative society and carried racial and moral implications far beyond a private indiscretion. “Anachoka mwa manyazi,” as the Chichewa phrase aptly captures, Banda departed Scotland not merely by choice but under the weight of shame. This episode complicates the sanitized portrayals of his life, revealing a man capable of both moral rigidity and personal transgression.

Following Ghana’s independence in 1957, Banda briefly relocated there to join his longtime friend and fellow Pan-Africanist, Kwame Nkrumah. At the time, Ghana was the epicenter of African political awakening, attracting intellectuals and nationalists from across the continent. It is notable that Nkrumah himself was married to a white woman, reflecting a broader trend among Western-educated African elites of the era. Similarly, Seretse Khama of Botswana had married a white woman, Ruth Williams, sparking international controversy. Such unions, while politically charged, were also symbolic of cosmopolitanism and resistance to colonial racial taboos.

When Banda eventually returned to Malawi, he arrived with a white companion, Ms. French. This relationship fit the prevailing pattern among some educated African men for whom marrying or associating with white women had become a marker of modernity, education, and global exposure. However, Ms. French later left Banda after becoming uncomfortable with his increasingly close relationship with Cecilia Kadzamira, who worked as a nurse at his Limbe clinic. Banda’s attachment to Kadzamira was intense and enduring, though never publicly formalized, revealing once again the contradictions between his public morality and private life.

Cecilia Kadzamira herself was engaged to Mr. Nthambala, a teacher at Robert Blake Secondary School. In a dramatic turn of events, Nthambala was awarded a scholarship to study overseas and was effectively banished, never to return home. “Analandidwa mzimai,” as the expression goes, his fiancée was taken from him through the exercise of raw power. This episode helps explain why Banda could never publicly acknowledge Kadzamira as his wife. To do so would have exposed the coercion and personal injustice underpinning their relationship, undermining the moral authority upon which he built his political persona.

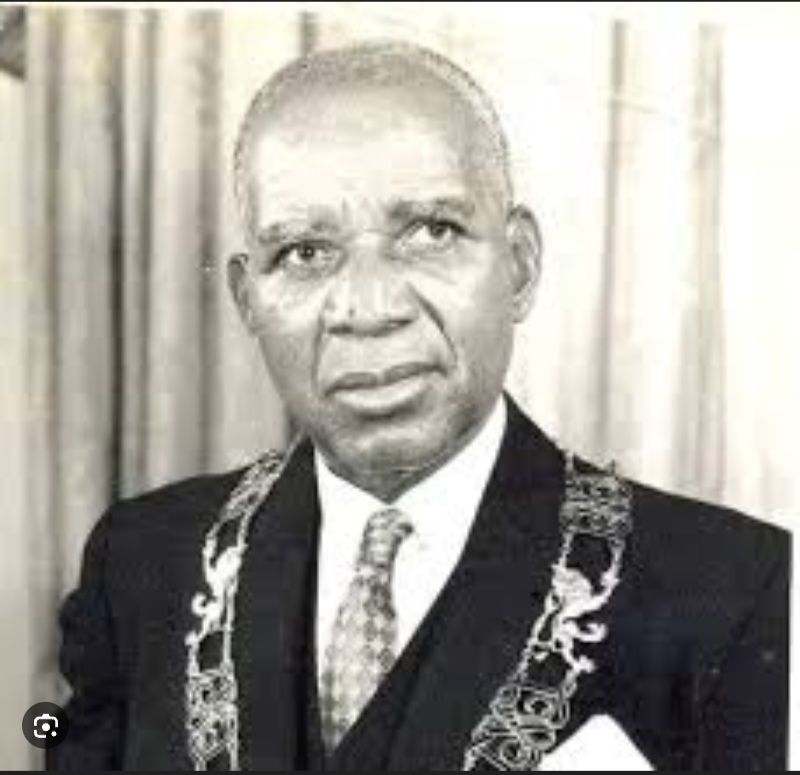

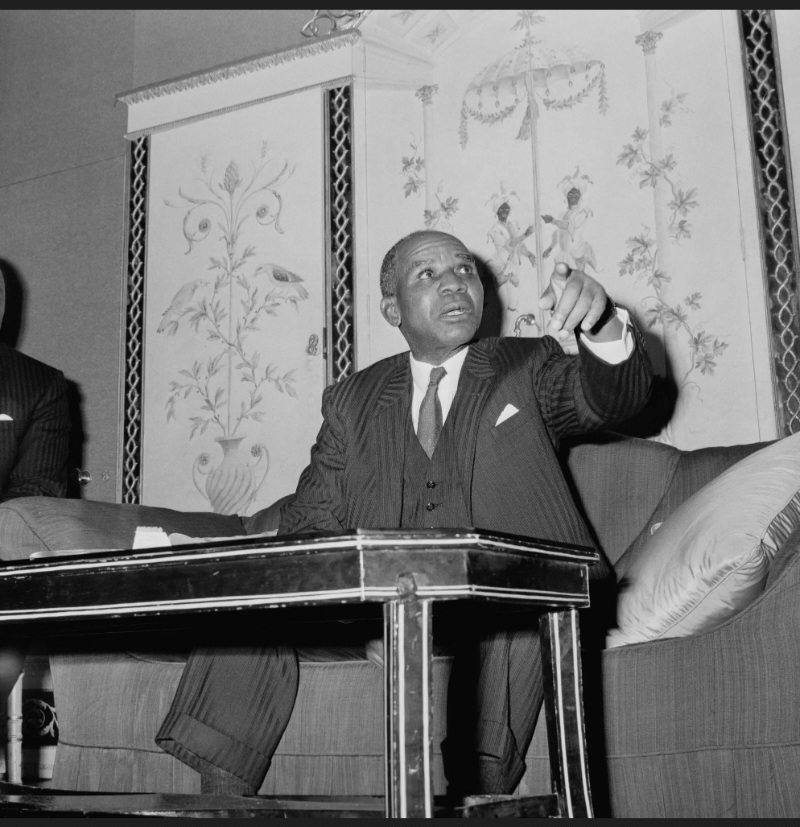

Banda with Kadzamira

Finally, it is important to address the circulation of images purportedly showing Banda with a wife, wearing wedding rings. These images are AI-generated and entirely fake. Banda was acutely aware of image-making and legacy, yet his personal life resisted neat categorization. In his own words, Banda explained that racism in the United States, professional limitations, and the wartime demand for doctors in Britain shaped his movements. His life was marked by ambition, discipline, and contradiction, a man who escaped racial oppression abroad, only to recreate authoritarian control at home. Understanding these complexities allows for a fuller, more honest reckoning with his more honest reckoning with his legacy. However this fact file is what his critics would always implore in quest to achieve political propaganda.

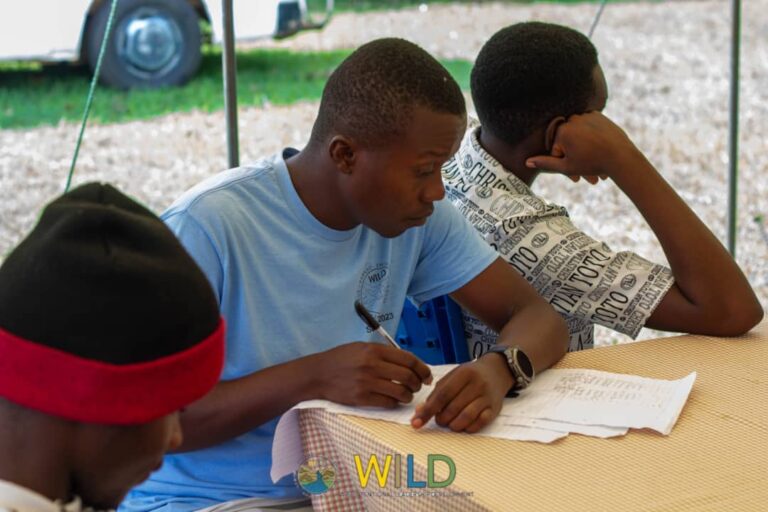

Banda while in Gweru prison with Joshua Mkomo (Zimbabwe), and Kaunda (Zambia)