By Mike Vladimir Chirwa

African literature emerged from deep historical wounds. Slavery and colonialism were not only systems of economic exploitation; they were instruments of cultural erasure that distorted African identities and silenced indigenous voices. For centuries, Africa was written about rather than allowed to speak for itself. In response, African literary thought developed as a counter-discourse thus, a way of reclaiming history, restoring dignity, and asserting humanity. Writing became both testimony and resistance, turning pain into purpose.

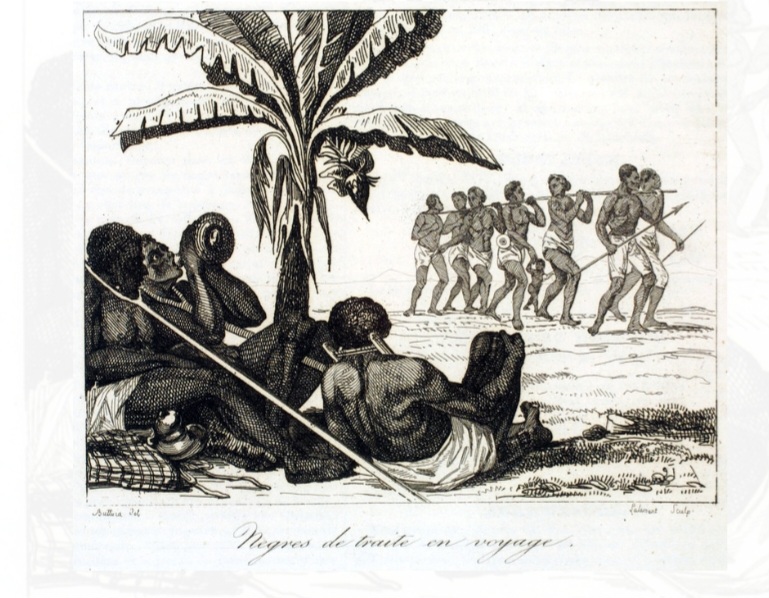

The transatlantic slave trade marked Africa’s earliest encounter with large-scale dehumanisation. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, millions of Africans were uprooted, commodified, and transported across the Atlantic. This violence fractured families, cultures, and memory. Yet it also produced the earliest African literary voices that sought to bear witness. Literature, in this period, functioned as survival, thus, a means of insisting on African humanity in a world determined to deny it.

Olaudah Equiano’s “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano” (1789) stands as a foundational text in African literary history. More than a personal autobiography, the narrative strategically humanises the enslaved African by emphasising intelligence, spirituality, and moral agency. By describing his Igbo upbringing and his intellectual development, Equiano directly challenged racist ideologies that justified slavery. His mastery of European literary form, combined with African experience, transformed the written word into a powerful tool of abolition and self-assertion.

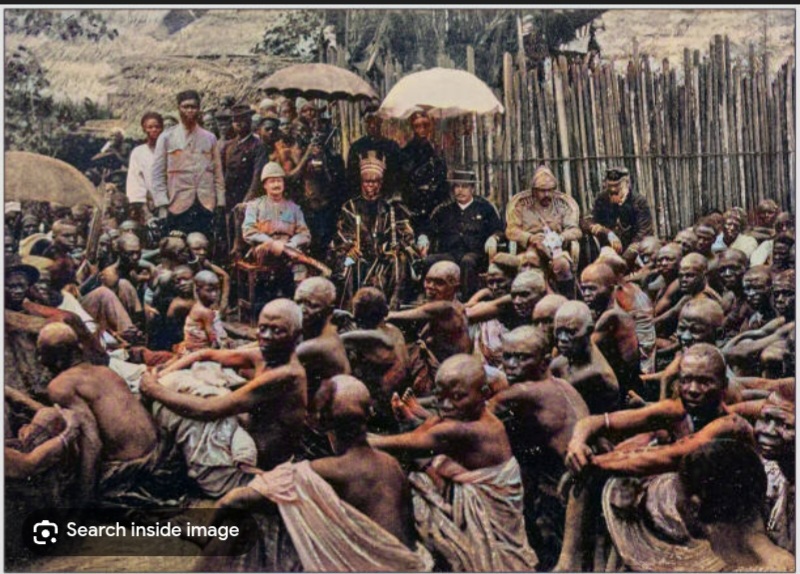

When slavery gave way to colonialism in the late nineteenth century, Africa entered a new phase of domination. Colonial rule extended beyond military conquest into language, religion, and education, systematically undermining indigenous cultures. African literature in this era became a site of cultural recovery. Writers sought to reconstruct precolonial histories and expose the violence of colonial intrusion. The struggle was no longer only for freedom of the body, but for freedom of memory and meaning.

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) represents a decisive moment in this literary reclamation. Achebe’s objective was corrective: to dismantle colonial portrayals of Africa as primitive and chaotic. Through the character of Okonkwo and the detailed depiction of Igbo social systems, Achebe presents a complex, morally ordered society disrupted by colonial forces. The novel’s tragedy symbolises the violent collision between cultures and asserts Africa’s right to narrate its own past with dignity and nuance.

As political independence spread across Africa in the mid-twentieth century, literature shifted its focus toward the failures of the postcolonial state. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood interrogate the betrayal of revolutionary ideals by new African elites who replicated colonial systems of exploitation. Ngũgĩ’s later decision to abandon English in favour of Gikuyu reflects a deeper ideological stance: that true decolonisation must begin with language, since language carries culture and worldview.

Ayi Kwei Armah approached postcolonial disillusionment through stark symbolism rather than realism. In The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born, he portrays a Ghana overwhelmed by corruption, filth, and moral decay. The novel’s disturbing imagery reflects the psychological residue of colonialism and the failure of independence to produce ethical renewal. Yet Armah’s work is not purely pessimistic; embedded within the decay is a yearning for regeneration and integrity, suggesting that moral rebirth remains possible.

Wole Soyinka expanded African literary resistance into drama and satire. In plays such as The Lion and the Jewel and Death and the King’s Horseman, Soyinka critiques blind Westernisation and cultural imitation. Through humour, irony, and ritual, he exposes the tensions between tradition and modernity. His work demonstrates that African literature need not rely solely on anger or tragedy; laughter itself can be a powerful weapon against cultural domination.http://www.wolesoyinkalecture.org.

In conclusion, slavery and colonialism did not silence Africa, they provoked its most enduring voices. From Equiano’s testimony to Soyinka’s satire, African literary thought evolved into a tradition of resistance, remembrance, and renewal. These writers transformed suffering into insight and art into activism. African literature today remains both a memorial and a manifesto: preserving historical truth while imagining freer futures. Through the healing pen, Africa continues to reclaim its voice and redefine its humanity.

African slavery at highest peak in 1950s to 1980s